We Can Do Better Than In-Person Public Comments

The main method of communicating to Stamford's Government hasn't improved in centuries. The City should invest in a digital verification system to enable online feedback from citizens.

In the 1960s, a cultural commentator named Marshall McLuhan published a book about how communications technology had altered the human consciousness.

Before widespread literacy, human beings learned everything through oral histories. We only knew things because they were told to us by another person. There was a social implication to our access to knowledge that meant to know anything you had to have ties to a community. After the printing press was invented — McLuhan explains — our species unlocked the ability to be individualists. Access to knowledge didn’t require social connections at all. You could read alone in the library. Nations saw this and funded education programs to spread literacy on very specific sets of ideas.

There was a period of time where new communications infrastructure created new communal activities. Families listened to President Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats by gathering around the radio and for a few decades the household was united around the television set. But then things shifted. Internet messaging boards, social media, and algorithmic content turned individualism into atomization where alternate realities emerged from your specific exposure to selected information.

All of these transformations in how we communicate made an undeniable impact on how human beings interacted with the world. The method of how we communicated had altered not only what was being said, but who we became based on how that information was communicated to us. Depending on how you got your information, your relationship with your fellow man was completely different.

This insight led McLuhan to famously conclude “the medium is the message.”

Stamford’s public comment system sucks

The medium for communicating with Stamford’s elected officials has been mostly the same since 1641. You need to show up in-person and talk to the board directly, which is so inconvenient most people don’t do it.

At the country’s founding it may have been a novel concept to allow the common man to address the government, but a lot has changed. The public is deeply familiar with alternative communications channels including phones, emails, or other digital-based messaging, but our local government is not. The City technically has the capacity to incorporate these mediums of communications, but the effort on technological innovation has been focused on bolstering in-person public comments rather than replacing them. We got a recorded video archive and Zoom participation before a dedicated email for resident concerns (or city staff dedicated to reading it).

The message of this medium is to make public participation difficult. If you want your voice to be heard — rather than filed into a folder that may or may not ever get read — you need to do the following ritual:

Look up the schedule for the next monthly board meeting.

Attend in-person at 7pm on a Monday night.

Wait up to 30 minutes for the pledge of allegiance, awards of recognition, roll call, and occasionally several minutes of “can you hear me? My Zoom isn’t working.”

Wait for all the other public commenters to finish — which may take a very long time if you see this guy there.

Condense your thoughts on public policy to 3 minutes, and don’t violate the other rules such as:

You can’t talk about anything that was previously the subject of a public meeting.

If you make the Board President upset they can cut you off.

This process already sucks and that might be why the proposal to make it even worse garnered two seemingly opposed opinion pieces that circle around the same point.

Public comments are already so difficult that anyone who would go through the trouble to give one is necessarily a rare individual — which naturally selects for people not representative of the public.

For example: The only in-person comment I’ve ever given was an attempt to prove the Board of Representatives participated in content-based discrimination, but fortunately/unfortunately Nina Sherwood knows the rules of free speech better than Carl Weinberg.1

The fact public comments are not representative of the public gives both political factions in Stamford what they want.

The extreme political minority gets the gratification of a lived delusion. Seemingly, most people are submitting public comments agreeing with their position. Except, it’s not most people it is most people who go through the trouble to speak at public meetings. This lethally combines with Connecticut’s minority representation laws to entrench stubbornness rather than moderation.

Meanwhile, the dominant political majority gets to thoroughly discredit public feedback so they can govern without concerning itself with the public’s opinions. Mayor Caroline Simmons has correctly identified this feature of Stamford’s media market which is why she is rarely quoted outside of press events in mainstream newspapers — and I imagine she will never respond to Feather Ruffler’s requests for comment.2

Public comments are already so difficult that anyone who would go through the trouble to give one is necessarily a rare individual — which naturally selects for people not representative of the public.

The solution is not to make minor adjustments to a medium of communication that sucks. In the words of Doug Stanhope, if the current system didn’t exist would you invent it? If you wanted a way to know what the public thinks about something, would you require a 30+ minute commitment at one of the most inconvenient hours of the day? Would you hope a group of volunteer politicians would choose to share critical feedback of themselves? No.

You would create a digital communications channel. Similar to Fix It Stamford but for general comments. You wouldn’t have a length restriction. You’d have city staff dedicated to measuring this feedback to identify trends in public perception and share that with elected officials.

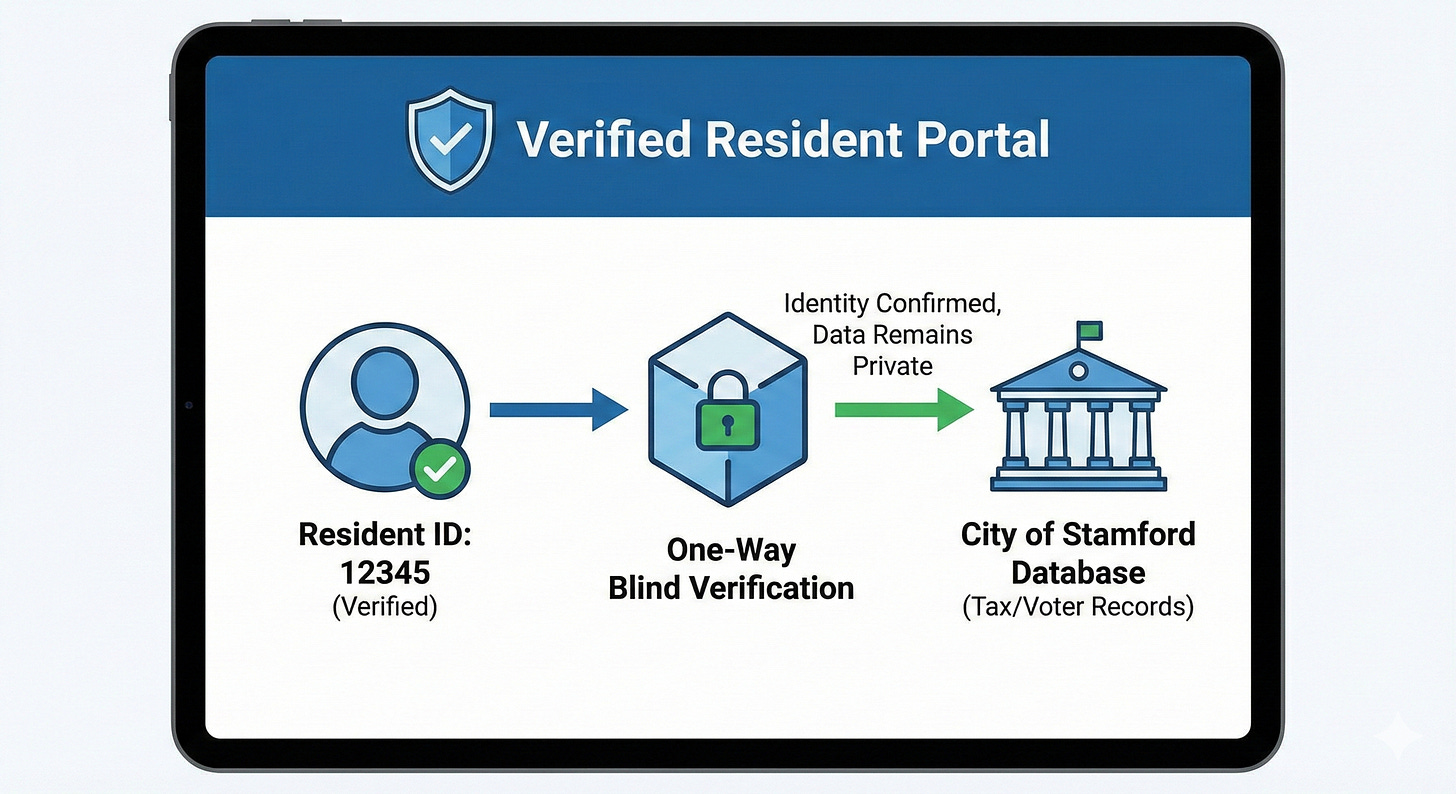

However, you would need to confirm the person submitting their concern is 1) an actual person and 2) actually lives in Stamford. A local solution is possible, but it’s a local solution to a international problem.

The internet cannot be trusted

It has long been a problem on the internet that traffic can be manipulated by “bots” — programs coded to engage with content as if they were human beings. This is why you’ve probably filled out a CAPTCHA and why CAPTCHAs have gotten more difficult since a decade ago. This has always been a problem on the internet, but the digital world crossed the metaphorical Rubicon of this issue in 2013. In that year YouTube’s fraud and abuse team found there was now more traffic from bots than actual human beings. YouTube calls this “the inversion.”

I call it proof of Dead Internet Theory.

Dead Internet Theory is a broad term that includes the massive influx of bot traffic, astroturfed manipulation of influencers, and the preponderance of state-funded actors pretending to be Americans. I personally believe this trend is relevant to the rise of anxiety and depression among young people and political extremism across all demographics. However bad the problem is now, it’s only going to get worse with the rise of AI slop.

Stamford has mitigated the risk to these problems because it has no digital communications infrastructure. To the extent the problems of dead internet theory seep into our politics, it’s because people deranged by the internet find their way into public comments through a process my future self described extensively last year. However, there are still examples of protests organized by people who do not live in Stamford.

These are legitimate reasons to distrust internet-based communications, but it’s not a reason to give up.

Digital representation requires digital verification

There is a local and federal solution to these problems, but it requires an uncomfortable re-examination of the internet’s core ideal — anonymous communication.

The internet was born from idealists who viewed all people as equal. In the digital world you didn’t even have a body to discriminate against. Your only identity was chosen by you through your alias (or “screen name”). In the real world, everyone bears the name given to them by their parents but in the digital world you decided how you chose to exist. It was a beautiful thing and for the first 25 years of my life I was one of those idealists. But then the internet died and most of the identities you see online are not crafted by self-actualized Americans but corporate or foreign bots designed to manipulate you.

The anonymous internet is not defined by Edward Snowden using the name Citizenfour to whistle blow on big government overreach. The anonymous internet is defined by thousands of bots compromising financial institutions or the dark web trading in cryptocurrencies to exchange child pornography and assassination contracts. Hell on earth exists and it is three taps away from the phone you keep in your pocket at all times.3

The federal solution to the Dark Web could be what I call the Bright Net. A second internet funded by the government that requires a digital verification to use at all. The Bright Net doesn’t need to replace the regular internet. It would be a second option for any person or business who wants to know everyone else on the digital landscape is an actual American.

Of course, this would mean the government knows more information about you.

The verification system would be one-way blind. Whatever entity was responsible for maintaining the system wouldn’t see “ID 1234” is tied to “Arthur Augustyn” but just that “ID 1234” is a real person. Alternatively, if we did include personal data — like email addresses — that would present its own opportunities. If every mailing list in the world was legally required to check this central system to see if I gave permission to email me, then I might actually see the day where all political parties and candidates stopped fucking emailing me.

We don’t need a federal solution to the local problem of making public feedback accessible and trusted.

Stamford already has the departments and staff to implement a digital verification system. In 2021, Stamford hired its first Chief Information Officer. This is essentially a position dedicated to improving technology at the City of Stamford. It’s a role common in a lot of businesses and the addition to our local government was an encouraging future-thinking proposal. My understanding is Stamford’s CIO has been primarily focused on upgrading our digital financial system and beyond that it would depend on additional initiatives from the mayor.

Stamford’s verification system already exists in some capacity. Every Stamford resident has unique tax information associated with their existence. Right now, it’s some file in a system but it could be abstracted into a long string of numbers similar to a bank account or credit card. Except, this string of numbers isn’t tied to getting access to anything valuable other than confirming you are a current Stamford taxpayer. The tax department already manages these files and the chief information officer could assist with the verification system. Both of these departments report to the Director of Administration (as does the “IT” department) and — wouldn’t you know it — Stamford is currently looking for a new Director of Administration.

Stamford’s verification system already exists in some capacity. Every Stamford resident has unique tax information associated with their existence. Right now, it’s some file in a system but it could be abstracted into a long string of numbers similar to a bank account or credit card. Except, this string of numbers isn’t tied to getting access to anything valuable other than confirming you are a current Stamford taxpayer.

A digital identity verification has already been pioneered by Estonia — which is somewhat familiar with the concern of malicious web-based actors since they share a border with Russia.

With the verification system implemented, the City could rely on any number of existing engagement tools — such as a simple Google form — and require the verified identification number for your submission to be counted.

If the City was concerned about hundreds or thousands of people visiting this feedback form, it could take a more conservative approach. The City could include a URL to a poll that’s included with the tax letter that goes to all property owners in the city. The content of this poll could be formally enshrined in Stamford’s charter along with a number of restrictions to prevent cynical political manipulations.

For example, I would personally recommend the following limitations:

The annual poll can have no more than 10 questions.

Any question added to the poll cannot be removed for 4 iterations of the poll (4 years).

Any question added to the poll will be added after the next 2 iterations of the poll (2 years).

The poll must include: How do you view the Mayor of Stamford? [Strongly oppose, oppose, neutral, support, strongly support]

The poll must include: How do you view the Board of Representatives? [Strongly oppose, oppose, neutral, support, strongly support]

Completion of the poll cannot be “incentivized” by the City of Stamford.

These limitations would prevent inconsistent data by adding/removing questions too frequently and also prevent incumbent politicians from adding their own question to opportunistically frame their own accomplishments.

Whether the city chooses to create a 24/7 form or an annual poll, either of these options are within the grasp of our current resources and does not require spending an hour of your life waiting to speak for 3 minutes.

Stamford goes its own way

I reached out to the authors of the opinion pieces responding to the public comment issue and gave a short pitch of the above solution — requesting their take on the idea. The responses are emblematic of the frozen political climate of Stamford and American politics in general. Each party has its “thing” and that’s what they focus on. There is no appetite to do anything beyond what has already been done somewhere else.

“A digital system, if thoughtfully designed, could complement existing rules by expanding participation to residents who are otherwise excluded by time, location, or format,” said Versha Munshi-South in an email to Feather Ruffler. “The challenge is ensuring that such a system enhances access without introducing new barriers around privacy, verification, or technological literacy.”

“Platforms like that can run tens of thousands of dollars a year, and Stamford already offers multiple ways for residents to reach officials,” said Dennis LoDolce in an email to Feather Ruffler. “For something that’s already fairly accessible, it’s worth asking whether we need a full platform at that scale.”4

These are pretty standard points of view from each respective party. Democrats are concerned about equitable access and Republicans are concerned about cost to taxpayers. These aren’t unreasonable responses, but I’m a bit surprised our most thoughtful voices in both parties defer to a standard point. I’m confident our community has more to say.

Stamford is completely in control of its own destiny and we should act like that. We have enough prosperity to earn the right to take some risks. Those big swings are what result in transformative gains for our community.

That’s why I started Feather Ruffler. The ideas around what Stamford should be as a city, as a government, or as a community are all boring. Stamford is completely in control of its own destiny and we should act like that. We have enough prosperity to earn the right to take some risks. Those big swings are what result in transformative gains for our community.

There is a saying among economists: “the scarcest resource in any market is information.” In the context of all new information moving to digital spaces — and most digital spaces are overrun with slop — Stamford could invest a negligible amount to gain an abundance of citizen-verified information.

More important than the content of this information would be the message of the medium: your local government has invested time and money to know what the public thinks.

Incidentally, both the Institute for Justice (IJ) and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) exist to sue municipalities for the exact type of rules Stamford has for public comments. If anyone wanted to push this issue, I would recommend submitting a case to either organization because the current rules are clearly unconstitutional.

Still sending them!

Fun fact: the City of Stamford was targeted by a crypto ransom scheme sometime before 2018. It was never reported on in the newspapers, but I believe the “solution” was the city paid some thousands of dollars worth of Bitcoin to the ransomer.

LoDolce’s full comment:

“I think it’s an interesting idea and could be beneficial if it’s done thoughtfully. If it is a similar system like Veoci (Fix It Stamford) where residents can submit feedback, track their messages, and see confirmation that concerns were received could improve transparency and convenience, especially for people who can’t attend meetings in person. That said, cost matters. Platforms like that can run tens of thousands of dollars a year, and Stamford already offers multiple ways for residents to reach officials. For something that’s already fairly accessible, it’s worth asking whether we need a full platform at that scale. A simpler alternative, could be a centralized online form on the city’s website that routes messages to the appropriate officials, could deliver many of the same benefits at a fraction of the cost. It’s also worth mentioning that it’s good practice for public officials to follow up with residents who reach out to them or speak during public comment. Even a brief acknowledgment can go a long way in making people feel heard and respected.

The key is expanding access without creating unnecessary expense or barriers, and without replacing in-person public comment.”