Market Rate Units Keep Stamford Rents from Skyrocketing

A panel discussion about housing suggested market rate housing units have kept Stamford’s rents from skyrocketing compared to other Connecticut communities.

STAMFORD — A panel of state and local housing experts addressed what policies have prevented rents in Stamford from skyrocketing at an event held at Ferguson Library on Jan. 21.

The panel was hosted by People Friendly Stamford — a local advocacy organization that’s mission includes housing abundance — as part of a screening of the documentary Fault Lines. Fault Lines portrays the story of a single housing development proposed in San Francisco. Relying on interviews with local reporters and national housing experts, the film contrasts the effort of a neighborhood coalition to block the housing development with a homeless man’s attempts to find stable housing. The film was shown in its entirety prior to the panel.

The panel featured President of Pacific House Carmen Colon, State Senate Majority Leader Bob Duff, and President of Garden Homes and Board of Finance member Richard Freedman. The panelists echoed comments shared at another housing event hosted at the Government Center last week, but provided more specifics about Stamford’s housing situation.

Supply and demand in Stamford’s local market

Policy discussion on housing often splits on the best method of lowering the cost of housing. One side focuses on “Affordable” housing, while the other focuses on “market rate” housing.

“Affordable” housing typically refers to housing units where the rent is set by the government. Market housing refers to housing units where the cost of rent is set by the owner of the housing unit. Local Stamford housing experts create a distinction between “capitalized Affordable” and “lower-case affordable.” Affordable units (capitalized) are units where rent is set by the government, while affordable units (lower case) are units with lower rent compared to other options.

Stamford’s “Affordable Housing Program” is the Below Market Rate (BMR) program. The BMR program directly interacts with market rate housing. The federal government’s Department of Housing and Urban Development identifies the area median income (AMI) for geographical areas. Based on this AMI, Stamford’s BMR program identifies an appropriate monthly rent limit.

For example, a new development that typically charges $2,500 for a 1-bedroom may also have several “BMR units” that are compelled to a lower rent based on HUD’s data on AMI. In Stamford, the majority of 1-bedroom and 2-bedroom units are set at 50% of the region’s AMI. This means the typical 1-bedroom in the BMR program is limited to $1,692 monthly rent, based on the 2025 policy.

The panel commented Stamford’s success has been its focus on market rate and “Affordable” housing units.

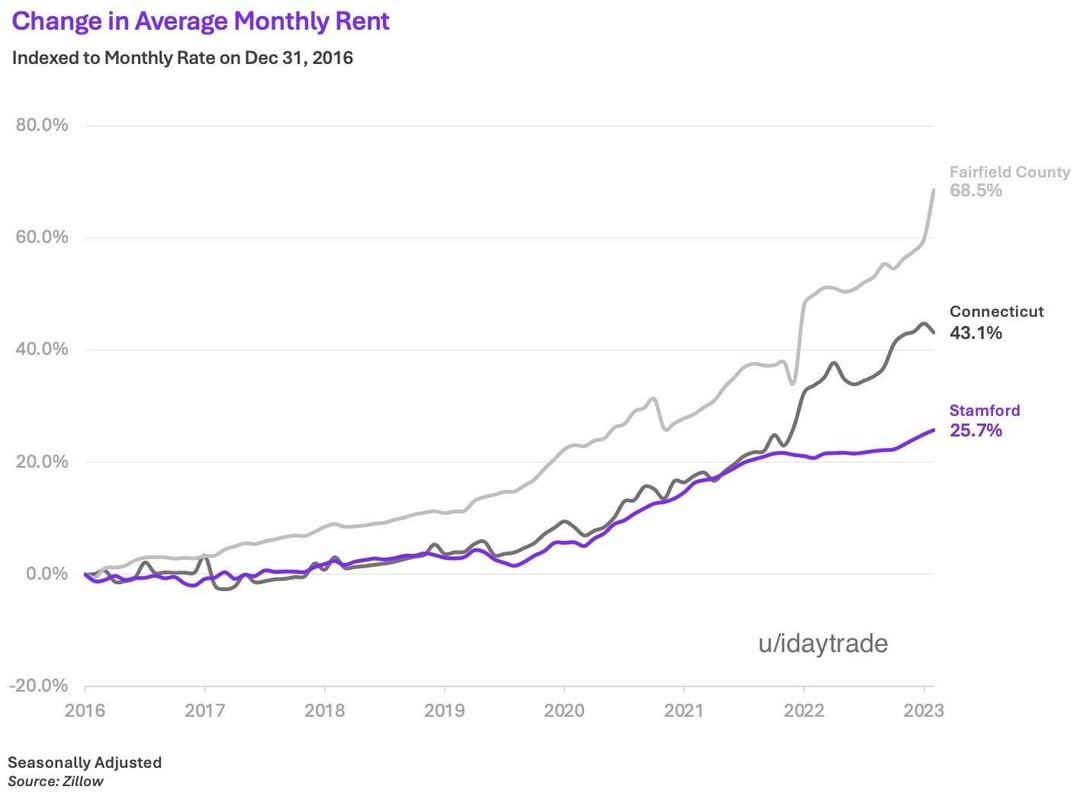

“Affordable housing is extremely important. That’s not enough,” said President of Garden Homes Richard Freedman. “We have to let market housing be built. We just need housing. I mean, we just need as much housing as we can get. Housing, housing, housing. We’ve proven it here in Stamford, right? Most of what gets built here is for the is for the top of the market, but I can tell you it’s held rents down here. So our rent growth here has been much slower than it has been in the rest of the state, because we’ve expanded the housing supply at a meaningful scale.”

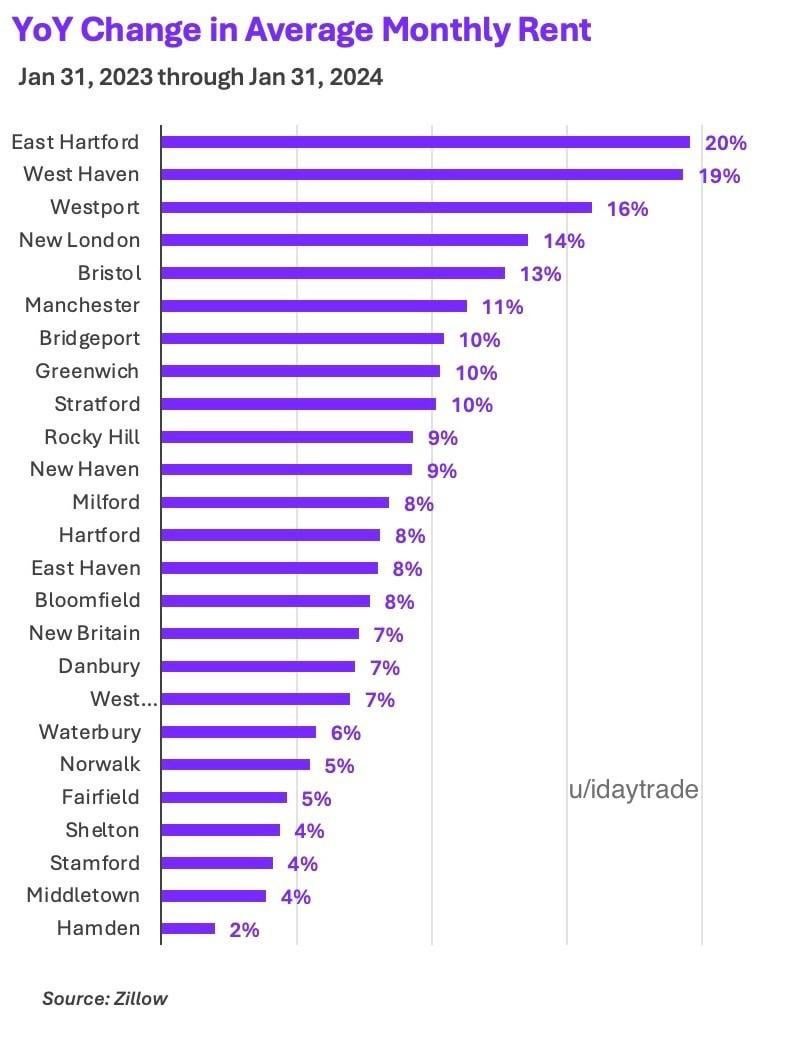

An analysis of monthly average rent in Connecticut cities showed Stamford had one of the lowest rent increases in the state. While Stamford’s rent increases are still significant, they are less than other communities that have not built market rate housing.

State incentives to offset local costs

The recently signed House Bill 8002 provides “carrots” to municipalities that agree to expand their housing plans.

“I do think it is [an] important component that we provide a carrot of an additional bump of school construction for communities like Stamford can go from 60 to 65%,” said State Senate Majority Leader Bob Duff. “I do think it’s important that we have another carrot of shaving off a half percent of interest rate for sewer connections, because we hear a lot of excuses from many towns around the state that they would build more housing if only they could get sewer connections. Okay, so we provided the tool to get a little money off that.”

School construction is a significant cost for Stamford since the mold crisis in 2018 revealed the need to remediate or rebuild a number of school buildings. Mayor Caroline Simmons has prioritized the new construction of Westhill High School which may end up costing more than $450M. Simmons announced in 2022 the State of Connecticut would cover 60% of the cost of the Westhill project.

Freedman said market rate housing can provide the benefits of more units without adding a cost to municipal budgets.

“Market housing [is] free. All you have to do is change the zoning,” said Freedman. Government doesn’t have to invest a nickel in that stuff.”

Regional imbalance of housing in Fairfield County

Stamford has expanded its housing inventory, but neighboring communities have not. The panel was critical of municipalities and elected officials who oppose housing.

“In most other places — let’s just list a few while we’re at it — Greenwich, New Canaan, Darien, Weston, Wilton, Westport,” said Freedman. “It’s not just the neighbors. It’s the elected officials. The first select people. The elected members of planning and zoning commissions or appointed members of planning and zoning commissions who oppose housing. The neighbors can make it worse, don’t get me wrong, but the elected leadership themselves don’t want housing. The dynamic you see in [Fault Lines] is that seemingly liberal people contort themselves into all kinds of rhetorical positions to justify their opposition. In this case, there was a lot of talk about environmental issues.”

In Fault Lines, the neighborhood group opposing the housing development initially frames their opposition as a lack of input from the community. Over the course of the film, the group discovers the dirt below the proposed housing development may have toxic chemicals. When the developer of the project performs testing that reveals there is not a significant health risk, the group maintains their view there is an environmental and health risk.

“Boy, I’ve run into those many times,” said Freedman. “Phony ones, by the way. The film makes that clear.”

Other panelists echoed Stamford has led on the issue of housing.

“There is not another city within our local communities at the moment that is doing everything that can be done to take care of the homeless population — especially during cold weather season,” said President of Pacific House Carmen Colon.

Pacific House provides overnight housing for men and young adults who are homeless. The organization claims to serve 60 to 85 men and young adults each night. Colon personally identified Simmons as a leader on the issue of housing for the homeless and asked her to “take her show on the road” for other mayors in Connecticut.

The event concluded with Duff and Freedman encouraging local residents to get involved in local politics.

“Please get involved,” said Duff. “Please show up at your planning and zoning meetings. A lot of times it’s very easy to wrangle people to say no. It’s harder to bring a lot of people to say yes.”

“What the senator said is very true. If you show up to a zoning hearing and you support something that can be effective,” said Freedman.